2016-02-11»

Coding underwater»

Part of my job is keeping up with a narrow subset of news. Being offline from Twitter has been strange for that: I hear news when people tell me. It’s a bit like when you come out of the swimming pool, and your ears are still full of water. I can still hear, but it’s muffled, at a distance. (“Now you have people to read Twitter for you,” says Liz consolingly.)

The lack of Facebook I haven’t noticed so much, but it was Twitter that was making me anxious. I’m already dealing with the consequences of a couple of minor twitter skirmishes second-hand. I can’t work out whether it’s easier to be calming, or whether I’m just a hypocrite for giving advice from the sidelines. Oddly, my continuing Tumblr habit is still pretty calming. Tumblr can get red hot for internecine warfare — I think possibly for the same porous private/public boundaries, contextless reblogging and hot-potato passing that Twitter enables — but I’ve adopted a somewhat lower level of people to follow, a distance away from my own circles. They’re not far away from the frontlines, and you occasionally hear a burst of gunfire, but in general it is quieter there.

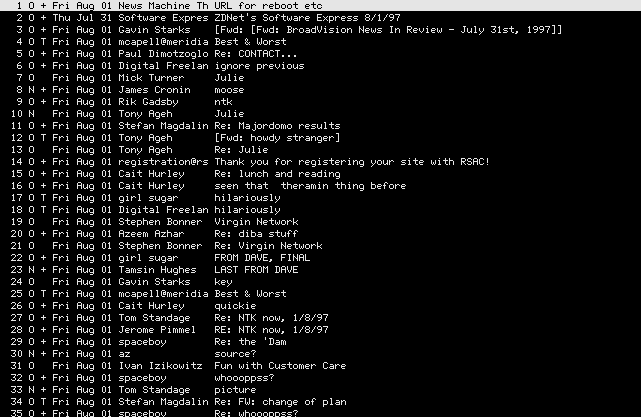

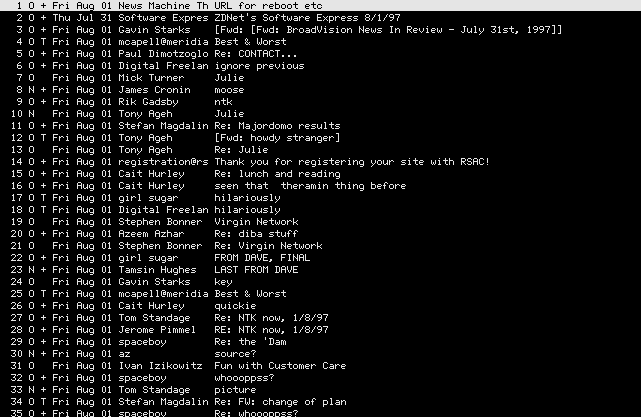

I’m taking the time to continue to do digital maintenance. I moved a bunch of very ancient mailspools into somewhere less vulnerable. The earliest is from August 1997; I still remember my annoyance when I lost the rest of them by failing to pick up my backup CDs from Wired when I left.

Looking through them, I wasn’t surprised that the volume was smaller (despite feeling overwhelming at the time). But even the subject lines seem shorter, look:

(Apologies for any privacy squick for anyone listed. Hey, it’s all meta-data, right?)

I blame wider screens. Of course what I should do now is actually do some data-mining of subject lines (and email sizes) and see how they’ve grown over time. ACTUAL CODE AND DATA.

Talking of code, here’s something I did for yesterday’s post. My vision of writing online always had some element of code mixed with words. It was part of what fascinated me about the the Dynabook. Back when it would sound funny rather than horrid, I would always say that I preferred my fiction with code examples.

So in yesterday’s blog post, there’s a tiny piece of code. It just randomly shuffles the multiple links to tone argument definitions, because I didn’t want to privilege one version of the story over another. If I’d had more time I would have worked out a way to make it a bit more visible, but as it is it ate about an hour of my time, which is why I’m not eagerly diving headfirst into learning email parsing and MATLAB right now. But I do want to try and integrate code into my writing more. Paul Ford can’t have all the fun!

I was pleased that I could just stick the code into my blog post, like it was just so much more HTML. My Javascript is rusty, so it took me a while to make it sufficiently self-contained. Here’s the code:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 |

// Takes a span, and randomly shuffles the destination of the links within it // Used to give equal weighting to many alternate link sources by randomly // changing which one gets the first link. // // I like <span class="ashuffled"><a href="http://www.ntk.net/">newsletters</a> // like <a href="https://www.getrevue.co/profile/azeem">this</a> and <a // href="https://tinyletter.com/danhon">this</a> and <a // href="http://internetofnewsletters.com/">this</a></span> // let postscript = function () { function shuffle_a_hrefs() { let classes = document.getElementsByClassName('ashuffled'); for (let a_span of classes) { var as = a_span.getElementsByTagName('a'); for(let i = as.length-1; i > 0; i -= 1) { let j = Math.floor(Math.random() * (i + 1)); let temp = as[i].getAttribute('href'); as[i].setAttribute('href', as[j].getAttribute('href')); as[j].setAttribute('href', temp); } } } function main() { shuffle_a_hrefs(); } if(window.addEventListener){ window.addEventListener('DOMContentLoaded', main); }else{ window.attachEvent('DOMContentLoaded', main); } }(); |

The main function does something called a Fisher-Yates shuffle, which I’d never heard about until I’d googled for how to do a shuffle in Javascript and found Frank Mitchell’s only way to shuffle an array in Javascript. Like everyone else, I code by googling these days.

Comments Off on Coding underwater

Emergent themes»

Look! Another no-publicity big-star tv-imitating-but-not-actually-tv feature! One more, and we shall have a trend!

Looks like the Flirble Organization has finally sublimated. I must write a proper obit for it, and plum.flirble.org, which held together so much of the early British Internet scene. In the exodus, I’m temporarily stashing my decades-old home domain, spesh.com on an Amazon instance until I can find it a better home.

It’s pretty hard to navigate AWS’s billing system, but when I did, I found that I’d been paying them 3 cents a month for … quite a while. Digging around, I found that I’d already used it as a potential escape route — I created a backup copy of oblomovka from the time of the Haystack Affair. I don’t know if I ever actually switched Oblomovka over to that after Oblomovka started getting a lot of hits, but it’s been patiently waiting to deal with the failover ever since.

I really can’t escape the distant past in this posting series, can I?

I’ve often wondered what I would have done differently with Haystack, if I had the opportunity to go back in time. It seems like it was one of the first of a general rise in the j’accuse mode of dealing with issues in public infosec projects. I don’t do that sort of activism any more, I think because it’s far too stressful on everyone involved, and had a lot of less than optimal outcomes. The hope is that you can get people out of a bad situation quickly with gentler strategies.

I think this may be another emergent theme, though: large explosions of public group emotional intensity may be suspicious. I am certainly suspicious of them, and these days I actively avoid such events, perhaps a little too much. They are contagious, and defining — and are often effective.

It feels to me that part of the current meta-debate online is how emotion should be moderated online. What emotions should you express? What are you allowed to do or say with emotion as your impetus? Who is showing emotion, and who is showing no emotion? (Think of the discussions about trolling and harassment, of civil behaviour and safe and trusted platforms.) Who is deploying emotion, who is authentically demonstrating their emotion, what emotions can you/should you/must you empathise with. Which ones can you/should you/must you reject?

When I am discussing something intensely online (yes that is a euphemism for “being in a flame-war”), I am very emotional. I pace around, am distracted, am twitchy. A few times I’ve asked the other person in the argument how they feel, and I’m surprised when people say that they’re not feeling any emotion at all. Even when they’re writing twenty replies in an hour. Can that be true? I assume good faith, even in an Internet fistfight, but I find it hard to imagine. I have also noted that I have had to explicitly say I’m feeling emotional, because my written style never indicates that, because I’m usually trying to maintain the form of a “correct” Internet discussion.

It feels like one of the shifts in the last few years has been the acceptability of expressing strong emotion in discussion, especially in public debate. When the first time the tone argument (&c, &c, &c, &c, &c) was identified as a trope in online discussion, was also the place where people realized that being angry didn’t always reduce your points to rubble. That anger might actually help emphasise and underline your point. That it might be dishonest and unbalancing to discredit or put it to one side.

Yet when I say that, I am suffixing the description of this shift with “at least in one of the subcultures that might make a claim to define the broad parameters of Internet discussion.”

But what does *that* mean, in an Internet of billions?

I just spent a good 20 minutes attempting to eke out the first use of the phrase “tone argument.” I’m pretty sure most of my trails end just pre-Racefail, a seminal moment which brought many of these issues to a head in the online English-speaking science fiction community. But note that despite carefully picking out a broad set of sources above, I know at least two of the authors personally, heck I live with one of the founders of the definition sites linked to, and am probably within two hops, or 500 miles of almost all of the other authors. All of them come from political viewpoints that, while scattered across a political spectrum, are shared by a tiny (but growing?) percentage of the population, even in the countries they write from. Those countries, meanwhile, are all Western, and all in the anglosphere.

That parochialism used to be less weird. But given that part of this discussion is about diversity, it begins to get weirder. Much of the form of Internet discussion is formed by the protocols, and later the platforms that dominated it early on. But is it also defined by broad cultural rules that spread through that medium? Barlow’s Declaration has its force because it came from the epicenter. Now it feels like the strongest, most generative part of the current zeitgeist is a critique of that centering. But much of its most forceful forms come from incredibly close to the same epicenters, the same sources.

(I do apologise if none of this makes any sense to you! These are disjointed notes on my thinking than anything more substantial or coherent. I’m also a little weirded out by often I refer to myself in this. I think there’s an eventual version of this that doesn’t sound quite so personal or egocentric, but for now I’m stuck with being inside my own head, a place full of my personal effects.)

Comments Off on Emergent themes