Currently:

Archive for the ‘San Francisco’ Category

2011-09-12»

song for noisebridge»

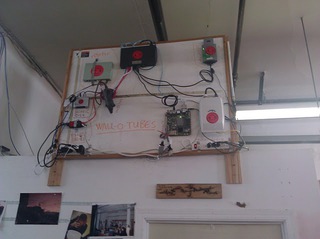

It is entirely appropriate that I came from hanging out at Noisebridge today with business cards from an Applied Anthropologist and an associate from the Institute of the Future. I also got to hang out with Dan Kaminsky and Eric Butler (of Firesheep fame). I wrote some Python, sat next to others writing Python in separate rooms (and by the side of a crowd learning machine learning, if that is a sentence). I yelled at someone, which I never do, and made up. Noisebridge drama! I worked at persuading someone that throwing out someone’s entire server rack (with server) onto the streets in the middle of the weekend, was an extremely poor – but not unpermitted – choice of things to do. I marveled at the genius of visually portraying the state of the internal network by nailing it to a wall, which had been some impromptu group’s impromptu project over the same weekend.

Around me ten people learned to solder, someone rebuilt the lighting system with a clutch of borrowed TED-5000s from the great Google PowerMeter shutdown , and I talked Syrian insider politics with someone wanted to teach Scratch to local kids. I gave tours to three groups, including the Applied Anthropologist, and gave the standard pitch: a hackerspace open to all, 24/7, where there was deliberately no rules and no leadership, just decision consensus and the ever-present sudo do-ocracy.

The Applied Anthropologist seemed fascinated, although really it’s hard to tell how rivetted people are when I can’t hear them over the rattle of my own obsessive proclaiming. I sincerely hope he is interested. I’ve often craved a Noisebridge in-house anthropologist, because Noisebridge is deeply, deeply culturally weird, and needs someone to unpick how it even stays in the air.

It’s a hybrid of cold war Berlin radical politics, maker culture, defcon-with-issues emotionality, FSF/EFF idealism, and just San Franciscan High Weirdness. It’s created press passes and space projects and mushrooms and robots. It’s run like an anarchist collective, if all the anarchists were asocial individualists who try to fix problems by throwing technology at them. We put off actual anarchists, because people come to the consensus meetings with T-shirts saying “I BLOCK” and frequently improvise ad-hoc solutions with powertools. In some sort of karmic test, I once had to eject a Buddhist monk from the space.

It provokes a huge range of emotions, and not just within me. Right now, it seems like an engine for generating social ideas, both stupid and painful and inspiring and positive and strange. Lots of people burn out from it, which I totally understand; I think I have only survived this long because I am so crispy for dozens of previous burn-outs. But I watch lots of people continually burn outward from it, or who re-ignite their passions from it, or save themselves from far worse fates. Its most driven members go through huge cycles of love and hate, which I think power the place with their alternating currents. If you’re in San Francisco, I’ll give you a tour.

Comments Off on song for noisebridge

2010-09-14»

Haystack vs How The Internet Works»

There’s been a lot of alarming but rather brief statements in the past few days about Haystack, the anti-censorship software connected with the Iranian Green Movement. Austin Heap, the co-creator of Haystack and co-founder of parent non-profit, the Censorship Research Center, stated that the CRC had “halted ongoing testing of Haystack in Iran”; EFF made a short announcement urging people to stop using the client software; the Washington Post wrote about unnamed “engineers” who said that “lax security in the Haystack program could hurt users in Iran”.

A few smart people asked the obvious, unanswered question: What exactly happened? Between all those stern statements, there is little public information about why the public view of Haystack switched from it being a “step forward for activists working in repressive environments” that provides “completely uncensored access to the internet from Iran while simultaneously protecting the user’s identity” to being something that no-one should ever consider using.

Obviously, some security flaw in Haystack had become apparent. But why was the flaw not more widely documented? And why now?

As someone who knows a bit of the back story, I’ll give as much information as I can. Firstly, let me say I am frustrated that I cannot provide all the details. After all, I believe the problem with Haystack all along has been due to explanations denied: either because its creators avoided them, or because those who publicized Haystack failed to demand them. I hope I can convey why we still have one more incomplete explanation to attach to Haystack’s name.

(Those who’d like to read the broader context for what follows should look to the discussions on the Liberation Technology mailing list. It’s an open and public mailing list, but it with moderated subscriptions and with the archives locked for subscribers only. I’m hoping to get permission to publish the core of the Haystack discussion more publicly.)

First, the question that I get asked most often: why make such a fuss, when the word on the street is that a year on from its original announcement, the Haystack service was almost completely nonexistent, a beta product restricted to only a few test users, all of whom were in continuous contact with its creators?

One of the many new facts about Haystack that the large team of external investigators, led by Jacob Appelbaum and Evgeny Morozov, have learned in the past few days is that there were more users of Haystack software than Haystack’s creators knew. Despite the lack of a “public” executable for examination, versions of the Haystack binary were being passed around, just like “unofficial” copies of Windows (or videos of Iranian political violence) get passed around. Copying: it’s how the Internet works.

But the understood structure of Haystack included a centralized, server-based model for providing the final leg of censorship circumvention. We were assured that Haystack had a high granularity of control over usage. Surely those servers blocked rogue copies, and ensured that bootleg Haystacks were excluded from the service?

Apparently not. Last Friday, Jacob Appelbaum approached me with some preliminary concerns about the security of the Haystack system. I brokered a conversation between him, Austin Heap, Haystack developer Dan Colascione and the CEO of CRC CRC’s Director of Development, Babak Siavoshy. Concerned by what Jacob had deduced about the system, Austin announced that he was shutting down Haystack’s central servers, and would keep Haystack down until the problems were resolved.

Shortly after, Jacob obtained a Haystack client binary. On Sunday evening, Jacob was able to conclusively demonstrate to me that he could still use Haystack using this client via Austin’s servers.

When I confronted Austin with proof of this act, on the phone, he denied it was possible. He repeated his statement that Haystack was shut down. He also said that Jacob’s client had been “permanently disabled”. This was all said as I watched Jacob using Haystack, with his supposedly “disabled” client, using the same Haystack servers Austin claimed were no longer operational.

It appeared that Haystack’s administrator did not or could not effectively track his users and that the methods he believed would lock them out were ineffective. More brutally, it also demonstrated that the CRC did not seem able to adequately monitor nor administrate their half of the live Haystack service.

Rogue clients; no apparent control. This is why I and others decided to make a big noise on Monday: it was not a matter of letting just CRC’s official Haystack testers quietly know of problems; we feared there was a potentially wider and vulnerable pool of users who were background users of Haystack that none of us, including CRC, knew how to directly reach.

Which brings us to the next question: why reach out and tell people to stop using Haystack?

As you might imagine from the above description of Haystack’s system management, on close and independent examination the Haystack system as a whole, including these untracked binaries, turn out to have very little protection from a high number of potential attacks — including attacks that do not need Haystack server availability. I can’t tell you the details; you’ll have to take it on my word that everyone who learns about them is shocked by their extent. When I spelled them out to Haystack’s core developer, Dan Colascione late on Sunday, he was shocked too (he resigned from Haystack’s parent non-profit the Censorship Research Center last night, which I believe effectively kills Haystack as a going concern. CRC’s advisory board have also resigned.)

Deciding whether publishing further details of these flaws put Haystack users in danger is not just a technical question. Does the Iranian government have sufficient motivation to hurt Haystack users, even if they’re just curious kids who passed a strange and exotic binary around? There’s no evidence the Iranian government has gone after the users of other censorship circumvention systems. The original branding of Haystack as “Green Movement” software may increase the apparent value of constructing an attack against Haystack, but Haystack client owners do not have any connection with the sort of high-value targets a government might take an interest in. The average Haystack client owner is probably some bright mischievous kid who snagged it to access Facebook.

Lessons? Well, as many have noted, reporters do need to ask more questions about too-good-to-be-true technology stories. Coders and architects need to realize (as most do) that you simply can’t build a safe, secure, reliable system without consulting with other people in the field, especially when your real adversary is a powerful and resourceful state-sized actor, and this is your first major project. The Haystack designers lived in deliberate isolation from a large community that repeatedly reached out to try and help them. That too is a very bad idea. Open and closed systems alike need independent security audits.

These are old lessons, repeatedly taught.

New lessons? Well, I’ve learned that even apparent vaporware can have damaging consequences (I originally got re-involved in investigating Haystack because I was worried the lack of a real Haystack behind the hype might encourage Iranian-government fake Haystack malware — as though such things were even needed!).

Should one be a good cop or a bad cop? I remember sitting in a dark bar in San Francisco back in July of 2009, trying to persuade a blasé Heap to submit Haystack for an independent security audit. I spoke honestly to anyone who contacted me at EFF or CPJ about my concerns, and would prod other human rights activists to share what we knew about Haystack whenever I met them (most of us were skeptical of his operation, but without sufficient evidence to make a public case). I encouraged journalists to investigate the back story to Haystack. I kept a channel open to Austin throughout all of this, which I used to occasionally nudge him toward obtaining an audit of his system, and, finally, get a demonstration that answered some of our questions (and raised many more). Perhaps I should have acted more directly and publicly and sooner?

And I think about Austin Heaps’ own end quote from his Newsweek article in August, surely the height of his fame.”A mischievous kid will show you how the Internet works”, he warns. The Internet is mischievous kids; you try and work around them at your peril. And theirs.

15 Comments »

2010-03-19»

what i did next»

For a moment, climbing out of the too-fresh sunshine and with the taste of a farewell Guinness still on my tongue, slumping into the creaky old couch in the slightly grimy, Noisebridge to write something from scratch, San Francisco felt like Edinburgh in August, a day before the Festival.

Edinburgh for me was always the randomizer, the place I hitched to every year, camped out in, and came out in some other country, six weeks later, with hungover and overdrawn, with a new skill or passion or someone sadder or more famous or just more fuddled and dumber than ever.

Today was my last day at EFF. Just before our (their? Our.) 20th birthday party in February, where I had the profoundly fannish pleasure to write and barely rehearse a 30 minute sketch starring Adam Savage, Steve Jackson, John Gilmore, me in my underpants, and Barney the Dinosaur, I callously told them I was leaving them all for another non-profit. We commiserated on Thursday, in our dorky way, by playing Settlers of Catan and Set and Hungry Hippos together. They bought me money to buy a new hat. I logged off the intranet, had a drink, and wandered off into a vacation.

In April, after a couple of weeks of … well, catching up on my TV-watching, realistically … I’ll be kickstarting a new position at the Committee to Protect Journalists as Internet Advocacy Coordinator.

I’ve known the CPJ people for a few years now, talking airily to them about the networked world as they grimly recorded the rising numbers of arrested, imprisoned, tortured, threatened and murdered Internet journalists in the world. Bloggers, online editors, uploading videographers. Jail, dead, chased into exile. As newsgathering has gone digital, it’s led to a boom in unmediated expression. But those changes have also disintermediated away the few institutional protections free speech’s front line ever had.

CPJ has incredible resources for dealing with attacks on the free press on every continent: their team assists individuals, lobbies governments at the highest levels, documents and publicizes, names and shames. They were quick to recognize and reconfigure for a digital environment (you have to admire an NGO that knew enough to snag a three letter domain in ’95). Creating a position for tackling the tech, policy and immediate needs of online journalism was the next obvious step.

The question I had for them in my interview was the same that almost everybody I’ve spoken to about this job has asked me so far. On the Internet, how do you (they? We.) define who a journalist is?

The answer made immediate sense. While “journalism” or “newsgathering” or “reportage” as an abstract idea might seem problematic when cut from its familiar institutions, and pasted into the Internet… nonetheless, you know it when you see it. When someone is arrested or threatened or tortured for what they’ve written, if you can pull up what they said in a mailreader or a browser, it really doesn’t take long to identify whether it’s journalism or not.

What’s harder is untangling the slippery facts of the case — whether the journalist was targeted because of their work, or other reasons; whether it was the government or a criminal enterprise that did the deed; where the leverage points are to seek justice or freedom.

In those fuzzier areas, in the same way as EFF uses its legal staff to map the unclear world of the frontier into clear legal lines, CPJ uses its staff’s investigative journalist expertise to uncover what really happened, and then uses the clout of that reinforced and unassailable truth to lobby and expose.

Honestly, I’m still only beginning to map out how I might help in all this. I spent a week last month in New York where CPJ is based, listening to their regional experts talk about every continent, all the dictators, torturers, censors and thugs, all the bloggers and web publishers and whistleblowers.

I know I am starting on that ignorance rollercoaster you get when striking out into new territory. I can tell these people about proxies, AES encryption and SMS security, but I still can’t pronounce Novaya Gazeta, or remember what countries border Kenya. You surprise yourself with how much old knowledge becomes freshly useful, at the same time as you feel stupid for every dumbly obvious fact you fail to grasp.

I think part of my usefulness will come from writing more, and engaging more with the communities here I know well to explain and explore the opportunities and threats their incredible creations are creating today. At the same tie, I’m already resigned to taking a hit in my reputational IQ as I publicly demonstrate my ignorance (my friends in Africa and Russia are already facepalming, I can tell). Hope you’ll forgive me.

In the mean time, I’ll be setting up my monthly donation to EFF. I’ve said it before and I’ll bore you again, EFF are an incredible organization, made up of some of the smartest and most dedicated people I’ve ever met. I smugly joined in 2005 thinking I understood tech policy, and spent the next few years amazed at what it was like to live as the only person who didn’t have an EFF to help me understand what I was looking at and what to do about it. I guess I finally got the hang of juggling five hundred daily emails, a dozen issues refracted through dozens of cultures across the world. And I guess that’s aways the cue to switch tracks and reset to being dumb and ready to learn again.

Incidentally, EFF is looking for an IP attorney right now. I don’t know how many lawyers read this blog, but if you know a smart IP legal person who wants to randomize their life for the opportunity to become even smarter for a good cause, get them to apply. They won’t regret it, not for a minute.

7 Comments »

2009-03-24»

An Army of Adas»

I gave up picking just one woman in tech who has inspired me over the years. I certainly knew that I couldn’t list them all. Here’s a roughly chronological list, which breaks down at the end when I realise that there could be no end.

I worked a Saturday job as a teenager at an IBM dealership when I was around thirteen. The first professional programmer I’d ever met worked there. She was incredibly smart and calm, and I remember being very impressed that you could actually make a living wage coding, instead of having to hide away in your bedroom hacking up ZX Spectrum platform games until somebody mystically gave you a Jaguar.

To save time, I will now skip a little arbitrarily (hello, Verity Stob!) across a few decades.

Out of my entire generation of Net-inspired London geeks in the Nineties, Pouneh Mortazavi was the only with enough initiative to do what everybody else dreamed of: she upped sticks to San Francisco alone. First she worked at Wired, holding together their databases; thereafter she started the Flaming Lotus Girls. She was always like some George Washington of a self-collected militia, marshalling and deploying technology and resources, cajolling and inspiring.

My ex-wife, Quinn Norton, has a aircraft-carrier full of skills and virtues, but if I had to pick a technological trait I admire most in her, it would be her ability to see its historical context, as well as extropolate it into the far future (and also her Perl coding style, which is the weirdest damn thing I ever did see).

Leslie Harpold simultaneously drove up the standards of web design, usability, and common human decency online. She’s still missed.

Annalee Newitz and I worked at EFF, and shared a career in writing 1000 word pieces on 1000 year topics, before she finally ran off to join the io9 intergalactic circus and exploration unit. She’s the embodiment to me of the one of the sublime joys of technology: jumping into the deep-end with just a laptop and a head filled with implications, and asking smart questions until you know as much as the expert will admit.

Cindy Cohn, legal director, and Shari Steele, executive director, of the EFF: I simply can’t list how much you owe those two people — but free crypto, and a censorship-free US Internet is probably a good start.

Suw Charman-Anderson, the creator of Ada Lovelace Day deserves a place on this list just for that, but she’s takes her place here because of her work binding technology and civil liberties together as the co-founder of the Open Rights Group.

I suspect Valerie Aurora will be on many people’s Ada Lovelace Day lists. A kernel hacker who can write, and whose writing can make me laugh out loud or smack my head in revelation.

Liz Henry wields technology as it should be: a fire to protect what’s right, and a blast of fresh air to winnow out what’s wrong. I’ve never seen any quite so able to pounce on new tech and bring it swiftly to bear on a societal problem, as well as explain its uses to those who might otherwise be bypassed by this revolution.

Becky Hogge was ORG’s second executive director, and another forger of ideas. Astoundingly good at herding other geeks, tech wonks, and MPs into spaces where they could all understand each other.

I get far too much attention for doing one single lousy talk about “life hacking”, whereas Gina Trapani deseves all of the credit for turning a dumb idea into a a brilliant, long-lived work of real usefulness — and for cranking out the code.

On the same note, butshesagirl‘s Getting Things Done application, Tracks, got me through some tough times. I admire anyone whose managed to keep an open source project on course, but I was particularly impressed by bsag’s skills. I watched and I hope learned.

And now no time to talk about the community chops of Cait Hurley, Rachel Chalmers’ piercing analysis, Rebecca Mackinnon’s work at connecting the world, Sara Winge’s genius at O’Reilly, Anno Mitchell’s sardonic Web 2.0 charisma, Strata Chalup’s sysadmin and southbay knowledge, Kass Schmitt sailor and LISPer, Silona Bonewald’s politech savvy, Sumana Harihareswara’s geek-management hybridism, Ana Marie Cox’s snark, Cherie Matrix’s cultural vortex, Elly Millican’s web aesthetic, Wendy Grossman’s sceptical optimism, Desiree Miloshevic’s globe-trotting ICANNoclasm, the piercing tech analysis of Susan Crawford (now working at the Whitehouse!), Sarah Deutsch, Kim Plowright, Paula Le Dieu, Charlie Jane Anders, Violet Berlin, Biella Coleman, Alice Taylor, Sophie Wilson who designed my entire teenage life…

These people make the world my daughter, Ada, lives in. I’m honored she has such shoulders to climb.

This was posted as part of the Ada Lovelace Day project; if you’d like to read more, I enjoyed Liz and butshesagirl‘s entries, spent a long time thinking about this sad and all too typical story, and saved the story of En-hedu-Ana, mapper of the stars, for Ada’s next storytime:

The true woman who possesses exceeding wisdom,

She consults [employs] a tablet of lapis lazuli

She gives advice to all lands…

She measures off the heavens,

She places the measuring-cords on the earth.

Comments Off on An Army of Adas

2008-10-12»

politics in the city»

Walking down a Bernal Heights street, I heard a guy shouting from behind me to a woman in a garish, oversized white t-shirt with somebody’s name on it. “Hey, you guys are doing well — I see posters for Tom everywhere!”. The woman shouted back, “Thanks! Who are you walking for?” “Eric!” “Cool!”. Later, a bunch of bicyclists fly by in convoy, playing an upbeat latino tune on speakers, and waving flags for another candidate.

It’s election time in San Francisco. As well as the presidential election, there’s the usual Bible-sized selection of other plebiscites to be plebbicized, including the election of the supervisor for my local neighbourhood. You can decide whether you should vote for Eric or Tom or Eva or David or Vern or Mark or the other Eric by thumbing through the 268 page local voter guide here. I believe that’s on top of the 166 page State guide.

I was going to witter here a little about the vibrancy of American elections, and then I remembered where else I’ve lived where elections were this vivid and fun. When I was eight, I remember the cars driving around with loudspeakers balanced on top, and posters, and speechifying and lots of local excitement to a British election. I grew up in Basildon, a marginal constituency (Ohio-on-the-Thames, if you will), and ground zero for those wanting to extrapolate results from their glib little parodies of voting patterns. You had to admit though, both sides fought like prize-fighters for every voter there.

San Francisco is about as far away from a swing state as you can imagine (unless you mean between Cindy Sheehan supporters and Nancy Pelosi fans), but the internal city politics are gloriously internecine and bloody. Supervisors have a surprising amount of power: en mass they are a counterbalance to the major. One of them just pleaded guilty to take $84,000 in bribes. I admire the huge encyclopedia of political explanations that turn up on everybody’s doorsteps every election, as well as the miles of columnage in the local papers analysing the minutiae of the city’s internal politics. Even the alternative free papers here often have front covers with titles like “REVEALED: JUST WHAT THE HELL DOES DEPUTY VICE ALDERMAN DIFRAMBRIZI THINK HE IS DOING WITH THE MANHOLE COVER FINANCIAL ALLOCATION FOR FINANCIAL PERIOD 2007/2008?”. To give a less made-up example, I have just read a (genuinely fascinating, actually) three page piece expose on the fines builders have to pay for having their cones in the wrong place. It is all connected with police graft, of course.

I honestly wonder who reads all of this, and yet I love that it’s there. I was reading Linus Torvalds slightly agape bemusement at how uncivilized American elections are, and wonder: is it better that politics be such a loud carnival? Or would all this corruption go even more unnoticed if no-one was watching?

4 Comments »

2008-10-09»

hacker spaces and recessions»

It’s awful to say that there are parts of recessions that I rather like. Maybe it’s just familiarity: I came of age in the early eighties, and left college in the 1990-1994 recession. My sense of what’s important gets confused in upturns: everyone is talking all at once about matters that I just can’t get excited about, but I feel somewhat silly for even thinking they might be wrong. Then the recession comes, and all my clever cynicism is (selectively) rewarded. In a recession, the signal to noise ratio seems greater. It’s easier to pick out promising ideas, and it feels better for the soul if you can express optimism when everyone else needs some extra.

I bumped in Jake Applebaum today, and we talked a little about NoiseBridge, the San Francisco Hacker Space that he is helping to launch. It’s a little surprising that SF hasn’t had one before, but I think that’s partly because there are lots of informal, ad hoc spaces, and also because during boom times, there’s little need. Every start-up has a tiny piece of what you need to make a hacker space, and won’t give it up.

The timing to me seems perfect, though. It’s a good time to pool both resources and ideas: gather together everyone to work and talk together about their projects, and co-operate on relieving some of the burdens of getting ideas off the ground. I’ve already thought about how, given that I’m probably going to be moving into an even smaller space myself, how I could deposit some of my most valuable textbooks at NoiseBridge: saving me space, and increasing their use. A lot of people will be wanting to broaden their skills, or spryly cross over to wherever there is a demand for hackerish minds (I remember well the great Perl hacker bioinformatics migration of 2001), so crossover technology like a chemistry lab and dark room is useful.

Something I noticed about the old recessions – the eighties, the nineties, the noughts, was that technology became a route out of poverty and dead-ends: there’s a huge proportion of system administrators and programmers who never made it through college, or high school, and found themselves in Silicon Valley, being airlifted to a sustainable life by one another’s efforts. I imagine this will happen again in this recession too. If we hunker down to build what comes next, it’ll be good to do it in a place where teenagers can help lead the charge.

Now I’m thinking of backspace on the banks of the Thames: an engine that seeded excitement behind a bunch of art and business projects (especially those that could not decide which they were). Is there a new hacker space imminent in London, Edinburgh, Manchester or elsewhere? I think it’s about time. Plenty of city business spaces going spare and empty, soon! Lots of advice available!

2 Comments »

2008-08-15»

bandwidth and storage and europe and america»

After doing my reading into fiber in San Francisco, I’d learnt a couple of things: firstly, there’s a lot of fiber around, actually, and secondly, a lot of the fiber under me was owned by Astound, who bought it from RCN, San Francisco’s previously weak-as-tea competition to Comcast.

As it happened, he next day I got some flyers through the letter box from Astound offering 10Mbps for $60 a month. As I’ve been tottering along with 4Mbps/1Mbps for $55 with Comcast, I thought I should look into that.

Competition is a marvellous thing. Wherever in the US Comcast has been facing it, I discovered, they have been magically upping their rates to 16Mbps. Simply calling Comcast support and hinting I was going to shift caused them to mention this fact, and five minutes later, I’m running at around 20Mbps/3Mbps for $65 a month. Add to that the $170 terabyte turned up today, and I feel like I’ve just leapt up about twenty countries in some OECD chart. I guess what I should do now is call Astound and see if they will offer to move PAIX into my bedroom cupboard for $65.99.

Up until now, I’ve always assumed that the UK’s consumer bandwidth situation has been rather better than most of the US — a tidbit gleaned from smug Brit slashdotters, and envy-enducing reports from my friends about their DSL deal-shopping. The received opinion is that the US dropped the ball almost immediately after rolling out broadband, and was promptly outgunned by most of the rest of Europe, something that begging outside telcos for ISDN-level speeds in most of Silicon Valley confirmed for me.

Now, after spending a few minutes on Speedtest’s worldwide self-selected statistics, I’m not so sure. I was originally assuming there was some American-bias to the stats, but digging deeper that doesn’t seem to be the case. The US actually does pretty well compared to Europe (except for those bastards in Sweden, etc) these days.

One thing I’ve learnt is that nation-spanning preconceptions like this are often temporarily true, but not for half as long as they hang around. Pleasantly schadenfreuderish viewpoints have a lot of lag to them. Take mobile phone adoption in the US. When I first arrived here, the difference between US cellphone culture and the UK was stark, and I, like many foreign-media journalists, would frequently dine out on the gap. In 2000, you couldn’t actually consistently text people on other networks; nor would it be reasonable to expect a stranger to have a mobile phone at all.

Then, in I think about 2003, I was crunching some stats about the crappy cellphone penetration in the US for my European friends to gawp at. Instead of doing an us-and-them comparison, I did a time-based one. How far behind was the US chronologically from the UK? It turned out that the US had just crossed 50% of households owning a cellphone. Laughably small compared to 2003 Britain, where it was close to 80% (I am surely misremembering these stats, but bear with me). But nonetheless, pretty much exactly the same as 2000 Britain, my original basis for smugly lording it over the Yanks. America’s primitive phone culture was, it turned out, only as primitive as the futuristic super-advanced one I’d left three years ago.

Sure enough, when my family came to stay that year, my usual prattle about how Americans don’t have mobile phones like we do was swiftly undermined. “What are you talking about, Uncle?” said my annoyingly smart niece, “Look around you. They’ve all got mobiles.”. And they had, and my anecdotes were like drinking from yesterday’s half-empty, cigarette-filled party beers.

I think the same thing is happening with broadband. From 2000-2008 there was a much bigger consumer rollout in Europe than in the US, partly because of government-compelled competition in European telecom (and aren’t I a bad libertarian for even suggesting that), and some really terrible decisions both by business and regulators in the United States. But those differences are slowly closing out as both continents start reaching the limits of DSL and the current infrastructure.

I imagine folks will disagree, which is fine. I’m not entirely sure of the position myself. The real question is: how could we test this? Are the Speedtest stats enough on their own?

6 Comments »

2008-08-09»

Which is more stupid, me or the network?»

I was working late at the ISP Virgin Net (which would later become Virgin Media), when James came in, looking a bit sheepish.

“Do you know where we could find a long ethernet cable?” How long? “About as wide, as, well,” and then he named a major London thoroughfare.

It turned out that one of the main interlinks between a UK (competitor) ISP and the rest of the Net was down. Their headquarters was one side of this main road, and for various reasons, most of the Net was on the other. Getting city permission to run cable underneath the road would have taken forever, so instead they had just hitched up a point-to-point laser and carried their traffic over the heads of Londoners. Now the network was severely degraded, due to unseasonable fog.

The solution was straightforward. They were going to string a gigabit ethernet cable across the road until the fog cleared. No-one would notice, and the worse that could go wrong would be a RJ45 might fall on someone’s head. Now their problem was simpler: who did they know in the UK internet community had a really really long ethernet cable?

I cannot yet work out whether being around when the Internet was first being rolled out is a disadvantage in understanding the terrific complexities and expenses of telco rollout, or a refreshing reality-check. I can’t speak for now, but ten years ago, much of the Net was held together by porridge and string in this way.

(Also, in my experience, most of the national press, and all of the major television networks. All I saw of the parliamentary system suggested the same, and everything anyone has ever read by anyone below the rank of sergeant in the military says exactly the same about their infrastructure. Perhaps something has changed in the intervening ten years. Who knows?)

Anyway, I’ve been reading the San Francisco city’s Draft feasibility study on fiber-to-the-home, which is a engaging, clear read on the potential pitfalls and expenses of not only a municipal-supported fiber project, but any city-wide physical network rollout. I love finding out the details of who owns what under the city’s streets (did you know that Muni, the city’s bus company, has a huge network of fiber already laid under all the main electrified routes? Or that there’s an organization that coordinates the rental of space on telephone poles and other street furniture is called the Southern California Joint Pole Committee?)

It’s also amusing to find out Comcast and AT&T’s reaction to the city getting involved in fiber roll-out:

Comcast does not believe that there is a need in San Francisco for additional connectivity

and believes that the market is adequately meeting existing demand. According to Mr.

Giles, the existing Comcast networks in the Bay Area contain fallow fiber capacity that is

currently unused and could be used at a later date if the demand arises.

…

AT&T does not recognize a need for San Francisco to consider either wireless or FTTP

infrastructure. The circumstances that would justify a municipal broadband project simply do not exist in San Francisco. Service gaps are perceived, not real, according to Mr. Mintz, because AT&T gives San Francisco residents and businesses access to: DSL , T1, and other copper based services from AT&T and Fiber based services such as OptiMAN that deliver 100Mbps to 1 Gbps connectivity to businesses that will pay for it.

My interest in it is more about the scale of any of these operations. The city will take many years to provide bandwidth, and the telco and cable providers are clearly not interested in major network upgrades.

But does rolling out bandwidth to those who need it really require that level of collective action? I keep thinking of that other triumph of borrowed cables and small intentions, Demon Internet, the first British dialup Internet provider, who funded a transatlantic Internet link by calculating that 1000 people paying a tenner a month would cover the costs.

The cost of providing high-speed Internet to every home in San Francisco is over $200 million, the study estimates. But what is the cost of one person or business making a high-speed point-to-point wireless connection to a nearby Internet POP, and then sharing it among their neighbourhood? Or even tentatively rolling out fiber from a POP, one street at a time? I suspect many people and businesses, don’t want HDTV channels, don’t want local telephony, and don’t want to wait ten years for a city-wide fiber network rolled out: they just want a fast cable on their end, with the other end of the cable plugged into the same rack as their servers. And if stringing that cable over the city meant sharing the costs with their upstream neighbours, or agreeing to connect downstream users and defray costs that way, well, the more the merrier. At least we won’t have DSL speeds and be slave to an incumbent’s timetable, and monopolistic pricing and terms and conditions.

I don’t think I would even think such a higglety-pigglety demand-driven rollout would be doable, if I hadn’t seen the Internet burst into popular use in just a matter of months in much the same way. But is the network — and demand — still ‘stupid‘ enough to allow that kind of chaotic, ground-up planning? Monopoly telcos won’t back a piecemeal plan like that for business reasons; cities won’t subsidise it, I fear, because it’s beneath their scale of operation, is too unegalitarian for the public, and undermines their own control of the planning of the city. But if it is conceivable and it is cost-effective, neither should be allowed to stand in its way.

5 Comments »

2008-07-27»

living by a hill in san francisco»

I grew up in Essex. One of the many exciting things about Essex is that it is tremendously flat. My aunt and uncle lived in Derbyshire, and when we went there for holidays, I marvelled at the ravishing exoticness of real hills. Now I live in San Francisco, and I have my own hill, called Bernal Heights, which has wild flowers, one (1) microwave tower, coyote, lesbians and illegal soap-box derbies. I actually don’t live on Bernal Heights, being none of the preceding: I live in the neighbourhood of Precita Valley, which is about two foot away from Bernal Heights. (San Francisco neighbourhoods are about five feet by ten feet, and are mainly differentiated by differing property prices, native language, and whether their climate is tropical rainforest, saharan, or fogbound arctic tundra.)

Anyway, today Liz wondered what Precita meant in Spanish, and looked it up in a book. “Dude,” she said, “It means ‘damned‘. You live in the valley of the damned.” I refused to believe this, and looked it up on the Internet itself. People who live in Precita deny this, and claim we live in the Valley of the Dammed. The confusion between dammed and damned may have come from the location of San Francisco’s first sewer, which, as explained in this beautiful description of the city’s adventures in sewerage, was both.

We also discovered that Bernal Heights still has a few of the old prefab earthquake cottages that were built to house the homeless after the 1906 quake. We drove to a nearby shack (maps), and hummed and ahhed at its brutal simplicity and hardiness, and I took several photographs. When we got back we realised that we’d got the address wrong and we’d been admiring somebody’s very expensive apartment instead. It’s a fine line between shack and des. res. in SF.

6 Comments »