Currently:

Archive for the ‘Society’ Category

2023-03-14»

poles apart»

Exasperated, I once said to a friend: “You can’t behave like you’re right all the time!”.

She looked confused. “How else am I supposed to act?” she said.

Strange attractors

It’s unlikely that I’m correct on everything: even more unlikely when I’m in a minority. I don’t like music, much. But so many other people love music! So I’m probably making some sort of error in that, even if it’s just an error of taste, or a personal incapacity. My theories on the Russian people are heavily outweighed by the estimations of, at the very least, the Russian people, and many more besides. I have some funny ideas on how Brexit happened. The accuracy of those theories are, to some extent in my mind, inversely correlated with how funny they are to other people. I’m not saying that I let the world democratically override my convictions: but the lonelier I am in my convictions, the more suspicious I become.

Despite being politically engaged, I don’t really identify with the right or the left. But so many other people do! And their views seem, often, to be more coherent, more well-thought out, backed up by dozens of books and essays that make the connections I fail to make.

It doesn’t stop me thinking what I think, nor feeling that sense of intuitive agreement whenever I do stumble on someone who, randomly, thinks the same as me on topic. My sister once told me that long before she understood the details of politics, she knew what she felt about the matters of the day. Does that make her right? No, it makes her who she is. Should we fail to add our opinions to the contemporary discussion, just because in a hundred years time, a chunk of them — maybe crucial, fundamental parts of them — will have failed to pan out?

The big bang theory of polarization

Everyone worries about polarization, and online radicalization. But we don’t often seem to worry about our own process of radicalization. Like many of my friends, I’d characterise my politics as having grown sharper over time, in contrast to the softening that I’d been told to expect comes with age. Despite my neither-left nor right-ness, if pushed, I will say I’m an anarchist, for goodness’ sake! A market anarchist! They don’t make those in moderate sizes!

But even among the anarchists, I feel like I need to watch my lip a bit. I find it really easy, in group chats or polite gatherings, very easy to stumble out of the consensus. I don’t know whether this is just me. When someone confesses to feeling like they can’t really say everything they want, that this is what I think they’re touching on. It’s not like I think I’m going to be cancelled: It’s just easy to touch on a topic where disagreement hides.

Of course, this may just be the fricking anarchists. It’s not like it’s a milieu famous for marching lockstep in calm display of unified visions and solidarity. But I also see this fractiousness elsewhere; I see it everywhere.

I sometimes think of online polarisation as being how the inflationary universe was described to me once (and oh boy, if I’m wrong about some things, I really bet I’m wrong about the structure of the early universe). The universe is expanding, I was told, but from any one spot, you won’t see it expanding. You just see everything moving, on average, further apart. Like ink marks on the surface of a balloon that’s being inflated, the universe is always unbounded, but somehow the distances grow in every direction.

That’s what the world’s opinions feel like to me. Some of it is that the Internet provided us with better space telescopes to see across this universe: Europeans knew something of America, but now they hear directly from Americans, and vice versa. Who knew what evil lurked in the hearts of men, until NextDoor came along?

But some of it is more active: as our universe expands, we get to (whether we like it or not) explore that idea space. We can zoom off in new directions, alone or with strange new attractors. We wander into the woods, and then look back, and everyone is further away, because they have so many more choices that they could make.

I find this, in my impossibly optimistic way, rather lovely. I don’t know whether I’m right, but I’m out here, noodling around the Noosphere, reporting back like Major Tom.

In our lanes, bowling alone

Another, different, good friend of mine, as close as one can be, is much as I remember him when I met him at college. We spent a lot of our life together, and I can instantly connect on the rare occasions we meet. We bond on so many features of the modern world, and politely disagree on a few, too.

He is totally convince 9/11 was an inside job, steel girders and planted explosives and everything. Unlike, say, our attitude to the West Country, he gets very annoyed when I express any scepticism about this. He is exasperated that no-one he knows can see the self-evident truth. I asked for evidence, and one Christmas, he sent me videos. For that single holiday weekend, I was convinced of it too: then I snapped out of it. We avoid the topic now.

Our universe of opinions and facts and statements and intuitions is multi-dimensional. Like GPT (everything will be analogised to GPT for the next few months, get used to it), there are millions of vectors in this state space, n-dimensional distances that connect each idea to one another. It’s really easy to just scoot down one or two of these numbers — start where you or I grew up, and then just spin a couple of numbers on the million-chambered one-armed bandit, until we’re the same, except you’re now millions of miles away in a single direction. I’m in London, and you’re in London too, but hundreds of miles upward. We both stayed on the Greenwich Meridian, but you stayed in your flat near Greenwich, and I pivoted off to Algeria. The universe of possible opinions balloons: even if we start close, we fly apart.

So how do we even talk to each other any more? How do we tolerate such distances? How do we stop us all just drifting further apart, from our family, from our friends, from a collective society, into some sort of heat death, or worse?

When the polarisation truly began to hit in the United States, back in 2015, I read a lot about the Reformation in Europe. It’s hard to extract much solace from the 100 years war, but I did. The West crafted a ceasefire from the religious wars that spilled out from those 95 new axes’ of freedom. The United States, in particular, was an unexpected commitment between religious maniacs, so intolerant that they were physically as well as conceptually displaced thousands of miles away, maniacs who thought that their neighbors — only a little more distant than those crammed into Southern England or Holland — were literally irredeemable. Somebody wants you dead in 2023? These people thought you deserved to die, then burn in hell for all eternity.

The truce failed when it came to many other inhabitants of that continent; but just the re-closing of that impossible distance fascinated me.

I am, of course, messing around with GPT, Llama, Galactica, Pygmalion and the rest. (Did you know there’s a GPT-4chan? You’d think they’d be writing about that, in the grown-up newsprobably going to hell, and risked taking their children with thempapers, wouldn’t you? Do they even know what’s happening now, what’s heading straight for us, rappelling down toward our tiny island of human consciousness, down every one of those billion parameters?).

Anyway, one of the things I’m messing around with is to use GPT as a bridge across that gulf. I get it to take some post that I don’t like, that I can’t read because it irritates me so much, the thing that shuts me off from new or distant ideas, and I automatically ask my pet GPT to rewrite it so I won’t bounce off it. Not buy into it: but not be alienated by its apparent proximity or distance from the worlds I do believe I understand. Texts in Chinese, in Hindu; local beliefs expressed in sneers and in dismissals. Love I don’t understand, fears I can’t sympathise with.

In Greg Egan’s Diaspora, humans have differentiated radically across the universe. Faced with a threat that could destroy them all, they create vast human chains of fractionally differentiated, intermediate consciousnesses, long chains of translators that are just close enough to their neighbour on each side of the chain, that they can, across the gradient of thousands of identities, convey an idea to and from an utterly alien descendant of mankind.

That’s my model of what we need to do, already, and will need to do more, not less. We are becoming alien to each other: but we can build tools that let us work together across long distances, as we did once before.

None of us are entirely right, but we need to talk to each other to triangulate, find out what’s wrong, and fix it, together.

(1400 words)

Comments Off on poles apart

2019-02-17»

Stream of conscientiousness»

I had a list of new year’s resolutions this year, which I wrote and then forgot about, but at some level have been trying to complete ever since. Let me dig them up; hold on. Ah, here they are.

Well, I’m not losing any weight, but I am managing to live stream pretty often. I share a weird corner of the streaming world, where amateur programmers show strangers their screens and their faces while they do random coding. Mostly it happens on Twitch TV, which has cornered the market in esports and mass live video demonstrations of gaming prowess. Twitch TV also streams the long tail of what it used to call “Creative” — enthusiasts building PCs, drawing pictures, messing with clay, and growing chickens. After a mixed beginning (where you could see Twitch trying avoid turning into a video sexworker marketplace, or just troll central), Twitch has clearly developed a fondness for these corner cases. Maybe it’s because they hark back to when it used to be Justin TV, and people showing you things they did was all it had.

Anyway, I’m hovering at the bottom of the “Science & Technology” category(!), a long way away from the 13 million followers of gamers like Ninja, and honestly a fair bit below popular coders like Al “The Best Python Teacher I Know Of” Sweigart, game developers like ShmellyOrc, and even other Lisp-exploring streams like Baggers and the mysterious algorithmic trader Inostdal. It’s okay though. I’m doing this for my own entertainment and sanity: livestreaming, for reasons that I’m still trying to understand, snapped me out of depression a year ago. (It’s not called Code Therapy for nothing.) Plus I’ve always enjoyed playing to small rooms, if they’re full of good people.

Anyway, as they say, subscribe and follow, follow and subscribe. Set it up to notify when I’m streaming, and come sit with me sometime. We’ll have a safely mediated chat, through protocols and stacks and obscene amounts of bandwidth.

Comments Off on Stream of conscientiousness

2019-01-05»

capital mood»

I’ve been futzing around with LISPs. See how we say LISP like that, all in caps? That’s how I think of Lisp; it has this vague aura of pre-1980s aesthetic where capital letters where either teletype-obligatory, or an actual indicator of futuristic COMPUTER WORLD.

Case in computing is a funny thing, like a binary signal in the ebb and flow of fashion. When and why did Unix (UNIX™) shell commands adopt that lowercase chic? I still write my email address in lowercase, even on government forms that request all caps, out of a defiant alt tone — DANNY@SPESH.COM stinks of AOL, Compuserve, and doing it wrong.

Common Lisp, forged in the eighties, expected, like Lisp itself, to be timeless: Common Lisp has CAPITALS all over it. Not exclusively, though. I guess when you’re Guy Steele and you’re trying to bind together futuristic AI and McCarthy fifties experiments, smashing together upper and lowercase is the least of your temporal concerns.

Will upper case make a come back? MAYBE IT ALREADY HAS.

Comments Off on capital mood

2018-02-01»

geek old semi-formal»

I love this articleby Christine Peterson about her coinage of the term “open source”, not just for the story (which I’d known about, but never heard in detail), but for the tone of the piece. It’s written in what I generally think of as “Geek Old Semi-formal”: this precise, slightly low-affect, somewhat wry tone that seeks to depict the maximum number of factual points, in a simple but almost shockingly accurate way.

In pretty much everything I’ve done, I’ve fought with the hellish triangle of being readable, entertaining, and truthful. Sometimes you end up flexing the absolute clinical truth for one of the others: for instance, I don’t really “generally think” of Christine’s tone as “Geek Old Semi-Formal”. I just made that term up on the spot. I didn’t quite confess that earlier, because it sounded funnier to imply I’ve used this name, even just internally, for years.

Compared to just describing the tone flatly, I did very mildly better on the entertaining axis (at least in my own mind), probably just as readably, but really not as true. (It was also easier to write — because a term like that is actually exactly what I need for a title. Great, I’ll paste that into the title box up there, and maybe that will become the hook for others who reblog this.)

Anyway, where was I? Right: so, actually honest documents are rare, mostly unentertaining and largely unreadable. We rarely optimise for the absolute truth, because either one of “readable” or “entertaining” is more immediately valued, and rewarded.

Geek Old Semi-Formal is readable and true, at the expense of some of the fripperies of language that we associate with entertaining speech. It’s this beautiful upgrade of technical writing to convey conversation, stories, anecdotes, and the communal trivialities of our lives.

As part of my Plan 9 binge (did I tell you about my Plan 9 binge?), I’ve been reading lots of old Unix papers, which all aspire to this style. As the New York Times said in its obituary of Dennis Ritchie:

Colleagues who worked with Mr. Ritchie were struck by his code — meticulous, clean and concise. His writing, according to Mr. Kernighan, was similar. “There was a remarkable precision to his writing,” Mr. Kernighan said, “no extra words, elegant and spare, much like his code.”

I don’t want to say that computer geeks got this from Kernighan; I think that there’s a wide set of folks involved in factual-seeking professions and hobbies that hold similar aspirations, and end up admiring and adopting the same style.

This morning, I opened a mystery package delivered by the “browsing ebay auctions at 3AM”-fairy. It was a paper copy of this February 1980 issue of MICRO: The 6502 Magazine purchased for reasons of unstoppable nocturnal nostalgia.

I think even the august editors of MICRO would concede that the writing skills of its contributors were pretty variable. The year 1980 seems to be a seller’s market for 6502 periodical literature: There’s a full-page advert pretty much begging for people to write articles. (They’re paying $50-$100 a page, too, if you want to go back in time.) But for me, that variability is just a great opportunity to watch the Geek Old Semi-Formal style fail and crumble in different ways. The feigned jocularity! The laundry lists! The science paper formalism! I won’t point fingers, but you can flick through this copy of MICRO to see for yourself the rich panoply of Geek Old stylings.

It’s also a style I really have come to enjoy in face-to-face interactions too. There’s just something deeply comforting about sitting and talking slowly and precisely with someone, each of you carefully constructing entirely accurate sentences with little overall variation in tone or pace. Especially by contrast to the usual chit-chat of slapdashing word-sounds together and slinging them out your mouth in order to fill time and show off, between gurning physical expressions and uncontrollable emotional explosions.

Not that it doesn’t also work for emotions, too. I think of all the times someone I know has flatly, compactly and desperately clearly conveyed their experiences: remaining calm, grammatical and short-sentenced even as the tears stream down their face, and their life fell apart.

I wonder, too, why I associate it with older geeks (older than me, for sure). It smacks a little of the repressed-fifties model of male scientist, though I don’t think of it as entirely gendered; in real life, it seems as strange on men as women. And I see people younger than me adopting it, often comically until they get it right. It’s definitely a bit on-the-spectrum—but I’m not on-the-spectrum and I use it, and aspire to it.

Well, now I’ve felt it so strongly in Christine’s great piece, I’ll start looking for it more, in words and in conversation. And now I have a name to call it!

Comments Off on geek old semi-formal

2013-08-06»

On the Thoughts of Chairman Bruce»

So I’m reading the latest missive from Chairman Bruce Sterling about Snowden and Assange, and even though I have some history with the guy, I’m clapping along, because he always writes a fine barnstormer.

Then, like Cory, I get pulled up by this bit. He’s reeling off a list of names, from 7iber to Bytes For All. I recognise them. They’re a list of activist groups I work with. The names are from a project I’m working on.

This what he says about those groups, in passing:

Just look at them all, and that’s just the A’s and B’s… Obviously, a planetary host of actively concerned and politically connected people. Among this buzzing horde of eager online activists from a swarm of nations, what did any of them actually do for Snowden? Nothing.

Before Snowden showed up from a red-eye flight from Hawaii, did they have the least idea what was actually going on with the hardware of their beloved Internet? Not a clue. They’ve been living in a pitiful dream world where their imaginary rule of law applies to an electronic frontier — a frontier being, by definition, a place that never had any laws.

Well, let’s go through the Chairman’s list alphabetically, and see if they have any excuse for their lack of aid and woeful ignorance about the electronic frontier.

First on the list, 7iber works in Amman, Jordan. 7iber is so politically-connected that their own government banned them last month from Jordan’s domestic Internet. I’m not sure reaching out to them was ever going to nab Snowden a safe harbor in the Middle-East. Probably the opposite: after all, they were were one of the groups translating Wikileaks into Arabic back in 2010, which didn’t exactly endear them to the local states.

Next up, Access. Access has a base in the United States, where aiding Snowden would get you hauled in for questioning on an espionage charge. I note they’ve been in such “a pitiful dream world” about the rule of law they spent a sizeable chunk of the last few years campaigning (with EFF and CPJ and many others) to get https turned on for a huge chunk of the Internet, thereby protecting it — I’m sure entirely accidentally — from unlawful NSA taps. You know, the ones that EFF has been telling people about since 2006.

Similarly, Agentura.ru must be incredibly ignorant about the surveillance state, given that it’s been investigating and whistleblowing on the Russian and American security service for 13 years. Enough to be detained and questioned several times by Russia’s secret police.

But hey, that’s just words on the Internet, right? What we really need is less of that online guff, and more direction action, right? Like our next witness, Aktion Freiheit statt Angst, who have been protesting surveillance in Germany since 2006, when they inspired 15,000 people onto the streets of Berlin.

Maybe you can explain to them how they can better make the security state a bigger issue in Germany this year on September 7th, at Potsdamerplatz. I can’t imagine any of those people will be agitating for better treatment for Bradley Manning or Snowden this year.

Moving on: here’s a pic from those NGO types at the Bahrain Center for Human Rights.

That’s the back of Nabeel Rajab. He sort of knows a little about the surveillance state, because his electronic communications and phones were monitored after receiving this beating from the Bahraini government.He’s been imprisoned in part for his work on social networks.

Besides the imprisonment of Rajab, the Bahrain Center for Human Rights in general also has some idea about the risks of Internet surveillance, because elevenother twitter users in that country have been jailed because of anonymous tweets that were tracked by sending them malicious web addresses. Here’s their detailed report. Note that that particular report ends with an explanation of how you can defeat that kind of surveillance. You know, apart from that delusional rule of law.

Wrapping up those As and Bs, Bolo Bhi and Bytes for All are both conducting the most sustained and brilliant work I’ve seen in advocacy, fighting against surveillance and censorship in one of the countries most determinedly targeted by both its own government and the United States for anti-terrorist action: Pakistan.

The idea that these groups, who are fighting to keep the Internet defended in their own country, are supposed to drop their grassroots activism and start, I don’t know, hob-nobbing the people they are actively opposing in their own states to get Snowden a break, or have any illusions about the rule of law on the Internet right now, betrays a profound misunderstand about what digital activists actually do these days.

Online activists these days do policy work, but they do a lot more than that. They have to do a lot more than that, because these days what we do in the “electronic civ lib” world is actually defend real people targetted by this surveillance. It’s been like that since around about 2008, when all of this deeply stopped being theoretical. Because it’s around that time that we all started getting friends and colleagues on government watchlists, or getting thrown in jail as a result of surveillance or Internet activity.

And it’s weird that Bruce doesn’t know that things got this weird five years ago, because ten years ago, he predicted at least part of it. Here’s how another of his barnstormers, this time in 2002, to the O’Reilly Open Source Convention.

In times of adversity, you learn who your friends are. You guys need a lot of friends. You need friends in all walks of life. Pretty soon, you are going to graduate from the status of techie geeks to official dissidents. This is your fate. People are wasting time on dissident relics like Noam Chomsky. Professor Chomsky is a pretty good dissident: he’s persistent, he means what he says, and he’s certainly very courageous, but this is the 21st century, and Stallman is a bigger deal. Lawrence Lessig is a bigger deal.

Y’know, Lawrence, he likes to talk as if all is lost. He thinks we ought to rise up against Disney like the Serbians attacking Milosevic. He expects the population to take to the streets. Fuck the streets. Take to the routers. Take to the warchalk.

Lawrence needs to talk to real dissidents more. He needs to talk to some East European people. When a crackdown comes, that isn’t the end of the story. That’s the start of a dissident’s story. And this isn’t about fat-cat crooks in our Congress who are on the take from the Mouse. This is about global civil society. It’s Globalution.

Okay, that’s a bit over the top, even for a 2002 O’Reilly audience. But hey, a classic Sterling coinage! It’s “globalution”!

In the end, it wasn’t Lessig who got cracked down on by the US government. Ridiculous idea! No, it was his colleague, Aaron. Here they are at the time. They were both at that conference. Aaron left early, and so I think he missed that speech. He blogged about it though.

Bruce continues:

I like to think I’m one of your friends. That’s easy enough to say. But one of the true delights of the world of free software is that it’s about deeds, not words. It’s about words that become deeds when they’re in the box.

So, I remember when the Bradley Manning story broke. Here’s Bruce’s words (and deeds) at the time, when the techie geek finally and horribly graduated to official dissident:

Bradley Manning, was a bored, resentful, lower-echelon guy in a dead end, who discovered some awesome capacities in his system that his bosses never knew it had… [People just like Manning] are banal. Bradley Manning is a young, mildly brainy, unworldly American guy who probably would have been pretty much okay if he’d been left alone to skateboard, read comic books and listen to techno music.

In 1998, I was one of a handful of fresh-faced newly-minted cypherpunk activists in the UK, trying ineptly to stop the roller-coaster of the UK’s Regulation of Investigatory Powers Act (and in particular the bit that would outlaw strong encryption in the UK) from being passed.

Doing this kind of tech activism outside the United States was, and frankly still is, a little frustrating. Whenever there was any story about our corner of the political universe — digital wiretaps, online censorship, public key cryptography — it always seemed to be about what was happening in the US, and not the rest of the world. Back then, I felt we needed the US media and policy space to pay attention to our fight: because we felt, very strongly, it was a global fight.

One day, we saw that Bruce Sterling was coming into town for a book reading, and we thought: here’s our chance. Like good Nineties digital activists, we’d all read our Hacker Crackdown, and knew he might be a friend in getting some rip-roaring coverage in the heart of the beast. After horribly hijacking him from what looked a nice literary meal, we took him to heroin-chic dive bar in Soho, told him our problems, and begged him to help.

Forget defending crypto, he said. It’s doomed. You’re screwed.

No, the really interesting stuff, he said, is in postmodern literary theory.

Honest to God and ask my friends, it broke my poor dork heart. I listened to him talk for a few hours about what was research for “Zeitgeist”, and then we went home and fought off the outlawing of crypto without him, but with a tiny bunch of committed Brits, some of whom are still working on that fight today.

Fifteen years on, the world sucks, but some parts are a bit better. As Bruce points out with his As and Bs, I live as part of a far greater and interlinked world of what he called “global civic society”, who, behind the scenes or in front of the microphones, actually do work together to defend people like Snowden, build tools for decentralisation and privacy, and frantically try and work out how to make them work for everyone.

Some of us work on policy, some of us work in a myriad other ways to change the world, including whistleblowing. We try to minimize the number who get beaten up or killed. I don’t think any of us live in much of a dream world any more. Pretty much all of us are more cynical than you’d believe after seeing what’s gone down. And I know, given the odds, some of it looks pathetic sometimes, but believe me, we can the hardest critics on each other about that. They’d laugh me out of town if I ever said “globulution”, for instance.

And, as the good Chairman says, you do learn who your friends are.

7 Comments »

2012-05-25»

NTK, Fifteen Years On»

Give or take a few days, it was fifteen years ago that I hit send on the first official issue of NTK. I was hiding out at a start-up called Virgin Internet, trying to work out how to bring Usenet to the masses, or something. I added people to the mailing list by hand, but stuck “-l” at the end of the subscribe email address to make it sound like it was a proper listserv. I still hear people say “listserv”, occasionally, and it sounds like they’re saying “thee” or “gadzooks” or something.

People usually say at this point that it doesn’t seem like maxint years ago, but, to be honest, it does. It feels exactly fifteen years ago. What’s weird for me is that the three years before NTK came out feels even longer. 1994-1997 involved me going from being on the dole, to appearing in a one man show in the west end, doing TV, working at Wired, joining a startup. That, and the Internet went from being this funny little squeaky gopher thing to having internet addresses on adverts. On adverts! Which, incidentally, we all smugly knew would go away soon, because advertising was lying and the Internet was going to make lying impossible. Or something.

. What I wanted to tell you was that last year after I explaining someone how we were all too collectively lazy to do something to celebrate NTK’s 15th anniversary, that someone came up with a brilliant Minimal Viable Celebration. So, for the next ten years or so, if you subscribe to this newsletter, you’ll get a weekly copy of the NTK that came out fifteen years ago, totally unchanged. It’s like that thing where you get a copy of the Times’ front page for your birthday, except every week is your birthday! Or our birthday. Or something. The name, Anno NTK, comes from Simon Wistow. If it was your idea to do this, tell me!

As I say, it’s literally the least we could do. I actually suspect (and hope) that this will become a bit of a trend in itself. Just as early retrospective sites like the Pepys Diary are drawing to a close, I think there’s this rich unmined pile of early blog-o-mobilia, waiting to have a nice interface stuck on it. It would be great, for instance, to watch in real time all the bloggers who supported the Iraq war go through their transformations and justifications day by day, or watch stuff like DrKoop and the Industry Standard rise and fall once again. There are lots of weird echoes in the air right now. I really hope other people won’t be as lazy as us, and put a nice frontend on the past.

And meanwhile, thirty years ago, Usenet itself was beginning to outgrow the ability for a human mind to comprehend. Thank goodness the future was so close…

27 Comments »

2011-09-12»

song for noisebridge»

It is entirely appropriate that I came from hanging out at Noisebridge today with business cards from an Applied Anthropologist and an associate from the Institute of the Future. I also got to hang out with Dan Kaminsky and Eric Butler (of Firesheep fame). I wrote some Python, sat next to others writing Python in separate rooms (and by the side of a crowd learning machine learning, if that is a sentence). I yelled at someone, which I never do, and made up. Noisebridge drama! I worked at persuading someone that throwing out someone’s entire server rack (with server) onto the streets in the middle of the weekend, was an extremely poor – but not unpermitted – choice of things to do. I marveled at the genius of visually portraying the state of the internal network by nailing it to a wall, which had been some impromptu group’s impromptu project over the same weekend.

Around me ten people learned to solder, someone rebuilt the lighting system with a clutch of borrowed TED-5000s from the great Google PowerMeter shutdown , and I talked Syrian insider politics with someone wanted to teach Scratch to local kids. I gave tours to three groups, including the Applied Anthropologist, and gave the standard pitch: a hackerspace open to all, 24/7, where there was deliberately no rules and no leadership, just decision consensus and the ever-present sudo do-ocracy.

The Applied Anthropologist seemed fascinated, although really it’s hard to tell how rivetted people are when I can’t hear them over the rattle of my own obsessive proclaiming. I sincerely hope he is interested. I’ve often craved a Noisebridge in-house anthropologist, because Noisebridge is deeply, deeply culturally weird, and needs someone to unpick how it even stays in the air.

It’s a hybrid of cold war Berlin radical politics, maker culture, defcon-with-issues emotionality, FSF/EFF idealism, and just San Franciscan High Weirdness. It’s created press passes and space projects and mushrooms and robots. It’s run like an anarchist collective, if all the anarchists were asocial individualists who try to fix problems by throwing technology at them. We put off actual anarchists, because people come to the consensus meetings with T-shirts saying “I BLOCK” and frequently improvise ad-hoc solutions with powertools. In some sort of karmic test, I once had to eject a Buddhist monk from the space.

It provokes a huge range of emotions, and not just within me. Right now, it seems like an engine for generating social ideas, both stupid and painful and inspiring and positive and strange. Lots of people burn out from it, which I totally understand; I think I have only survived this long because I am so crispy for dozens of previous burn-outs. But I watch lots of people continually burn outward from it, or who re-ignite their passions from it, or save themselves from far worse fates. Its most driven members go through huge cycles of love and hate, which I think power the place with their alternating currents. If you’re in San Francisco, I’ll give you a tour.

Comments Off on song for noisebridge

2010-04-08»

Guy Kewney»

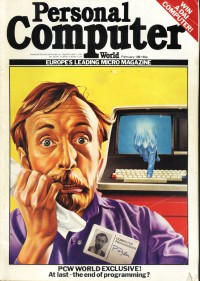

I don’t know why but from the age of eight to I think fifteen, I just assumed every drawing of a bearded man in or on Personal Computer World was meant to be Guy Kewney. He was the model journalist to me– why wouldn’t he also be the model for all those techies PCW’s graphic editors had to draw?

Not Guy.

As a pre-teen, I was a Personal Computer World kid. I loved the binding, the glossy cover, the thick tall pages, the sprawling reviews, the narrow columns of crazy computer classifieds that would stand like columns over pages and pages and pages of dot-matrix printed listings at the back, the love-hate relationship with the dull business business that would dog it into the grey IBM years, the arty covers, the bearded pundits. But most of all I loved reading Guy Kewney, the beardyist pundit of all.

Cromemco and Nascom, Siriuses and Osbornes. They seemed like far-off planets, and Kewney seemed like some pipe-smoking Dan Dare, giving a jocular downbeat debriefing in the mess, of his latest voyages with the Osborne or the COSMAC ELF, even when the most exciting software they did was inventory management. Kewney made even dull corporate machinations the stuff of high drama.

Aged 10 or 11, I would run around the house playing these elaborate fantasy games, muttering under my breath stage directions, and leaping from chair to chair in our living room. My adventures were set — and I am not joking here — in a 21st century where Apple-IBM and Sinclair-Acorn would heroically battle as giant zaibatsu corporations flying amazing robot battalions around in space. The dramatic climax would always involve me, as the captain of the flagship of the corporate fleet, controller of the inventory, master of the Science of Cambridge, shouting some secret password that would override all the command centers of the opposing army. My favourite Words Of Power in these fantasies was Angelo Zgorelec!, the mystical founder of PCW, whose name appeared on every issue’s masthead, and who I imagined to be a Tharg-like being of supreme wisdom (and great aural resonance).

But the person from whose writing I drew the strategies and the battles and the drama of those corporate tussles was Kewney.

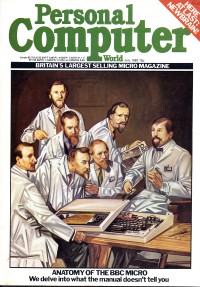

Also not Guy.

I still remember one of his columns. In it, Kewney, boggling at the effort to which software publisher Acornsoft had gone to copy-protect software , published the one-line command for rendering its primitive DRM completely useless. I don’t remember the details, but I do recall just stopping and staring and then laughing and rocking in glee at the audacity of it, and wondering why no-one ever said all those other hidden incantations that I was sure existed out loud in other newspapers and magazines. Then I watched him defend his decision after a barrage of outraged readers (swamped by those who cheered him on) chastised him the next month. It really stuck in my mind as this example of the power of words to unwind elaborate but unsustainable practices.

John Lettice says in his obituary that PCW had to pay Acorn for that Kewney column. They shouldn’t have. And if they had to because of the law, well then, the law was wrong: spelling out these magical words of power, causing corporate battalions to flash out of existence at a single, carefully-researched command, really was Kewney’s job, and he did it masterfully.

I met him once. I’d just started writing for PCW myself, in about 1990, only to discover that my rapid promotion to the flagship of the British tech mag fleet was because they’d sacked all the old guard in a labour dispute and were desperate to fill those gaping pages with cheap young new writers. I tagged along to some press conference and actually overhearing David Tebbutt or Christopher Bidmead or some other Elder God complaining loudly about the wide-eyed children who had stolen everyone’s jobs, yet wouldn’t stop babbling about how honoured they were to meet them.

After that, I always averted my eyes and ceased to bother the titans. When I finally met Kewney, I think I just stood awkwardly by his side, surely making him even more uncomfortable than he must have been.

Or looked. To me, some idiot kid, he did not look well. When I said this to equally squeaky kid co-worker, they told me he had always looked ill, a boney, pale man who was constantly being stabbed with allergies and posture problems, aches and pains and deadlines and all-nighters, triumphing over the all to file his copy mere hours before printers might knock down his door and wring his neck.

I found this hard to believe, because he always looked so erect and noble in his byline pictures. Also in all those cover paintings of him. And in those games where he flew across the corporate landscape, making the world change with a word or two. It just made him seem all the braver.

Now Guy Kewney is gone, and I have this beard, but the words of power are all gone too. And frankly, I do not feel too well myself. Timor mortis conturbat me.

5 Comments »

2010-03-24»

ada etc»

My real Ada Lovelace day piece goes out this Friday, in my Irish Times column. Honestly, it’s more an introduction to the idea (and why identifying diverse role models in tech is important) than a real story about a technologist I know, though it does mention a few.

I sort of sabotaged myself last year by listing forty women in tech who have inspired me, not realising I could have padded that out for an entire lifetime of ALDs. This year, I was going to salute the women of the EFF (without looking like I was just sucking up to my bosses), but Cory beat me to it with his profile of Cindy Cohn, EFF’s legal director.

(Then again, he didn’t mention EFF’s executive director, Shari Steele, who led the EFF to its current amazing successes; Jennifer Granick, its senior criminal lawyer (you want to watch this video to get an idea of Granick’s work); Marcia Hofmann who has leads many of EFF’s FOIA-related scoops, Gwen Hinze who steers EFF’s work at WIPO, against ACTA and beyond; Corynne McSherry who mends free speech when it runs into the DMCA; Eva Galperin who is your first responder when your digital rights catch on fire, Rebecca Jeschke who keeps obscure tech issues in the headlines where they belong; Alyssa Ralston who brings the money in, Katina Bishop who masterminds EFF’s awesome events and more awesome major donors; Leticia Perez and Andrea Chiang who make sure the briefs get filed and the bills get paid — and I sabotaged myself again, didn’t I?)

1 Comment »

2009-09-22»

you know who i blame? the lurkers»

All of these conversations I’ve been having online (as opposed to the dramatic monologues here) have had me thinking about the nature of online discussion, and confronting my own behaviour in them.

What are you like when you’re deep into an argument online? I have two sides: the one which you can see with my postings, which are long, mostly fiercely polite, quasi-grammatical, and, if I may say so, devastatingly reasoned.

You have to imagine me writing these, though, pacing around madly in my bedroom, muttering little speeches to myself and visualizing the horrible death of my correspondent in a hail of unavoidable saucepans. Also I drool, but only a little bit, and only from the mouth.

Is everyone like this? I don’t know, because people don’t like to talk about it. Recently, I’ve been looking at how people manage their own emotions when discussing online. It’s complicated, because the unwritten rules of much online discussion is that “if you emote, you lose”, and others that “if you emote, you win”. Either way, bringing emotions into it changes the game. But what the hell does winning and losing mean?

People talk about the disrespect and ferocity of online flame wars. I think it’s about audience. I think the novel nature of online discussions is that you have a passive, silent audience out there. I think that’s far significant than all that talk of anonymity, or the death of civilized discourse.

The closest equivalent to Internet discussion forums for me when I was young was Paddy, who I lived with. Paddy was a man who could argue for hours without coming up for breath. You’d say your triumphant logicbuster, and magically by the time you’d finished, he’d already have (verbally) posted a five page reply up in your face. I remember one night when I got so mad with him for his relentless logical verbal one-upping that the only snappy come-back I could devise with was to quietly leave the room, go upstairs to the bathroom, spray my entire face with shaving foam so I looked like a giant Michelin head, and then creep up behind him and go “ARRGH!”. I hold that I won that argument squarely and fairly. (You occasionally see this rhetorical device at Prime Minister’s Question Time.)

Anyway, what was annoying with Paddy, as I finally got him to admit one day, was that he wasn’t trying to convince you he was right: he was trying to convince a mysterious third-party.

There was no third-party in our arguments. When we got started both of us could empty a room faster than karoake-ing opera singer.

But on the public Internets, you’ve always got an eye to the third-party. Every talk you see online has an imaginary crowd around it, imaginarily clapping or stomping. Either way, you can’t just communicate these side-line emotions with the person you’re talking to, except by stumbling off into private email. Which is usually about as calming as going outside the bar for the fight. Actually, private email isn’t even private, because there is always this sense it will be magically reforwarded into the public view, exposing your vulnerability to the same audience.

Every discussion is a group monkey dance.

1 Comment »

petit disclaimer:

My employer has enough opinions of its own, without having to have mine too.