2026-01-07»

AI Psychosis, AI Apotheosis»

Novel terms with narrow definitions get fuzzier in meaning as they are more widely adopted. “Life hacks” did it, Cory Doctorow’s (this blog’s sole remaining reader, hi Cory) “enshittification” did it, vibe-coding did it. In fact, we probably need a new coinage to describe this effect so that we can then make it nearly meaningless.

It’s especially fun when the meaning of a term evolves at different rates and in different directions between communities, until nobody knows what anyone else is talking about. There was a time when I would bounce around social groups for whom “gaslighting” might mean, respectively, “offensively psychologically messing with someone until they started doubting their sanity”, “kinda lying to”, and, in some cases, “to illuminate one’s home with coal gas”. I never tried to get them all in the same room.

Anyway, I’ve noticed that “AI psychosis” is currently going through this split. For some people I know, it still means a clinically psychotic incident triggered by extended chatbot conversations — the intended definition. Boring. For others, I’ve heard it used to refer to anyone who thinks AI is useful. I.e., you don’t have to be mad to use AI at work, but you probably are, anyway. Usage: Oh, have you got AI psychosis too?

The latest application is interesting though: this winter holiday, many people I know of my age and demeanour — including self-declared AI skeptics, which, let’s face it, we mostly are — have had the time to lock themselves away and really dig in with the new state-of-the-art language models, LLMs like Opus 4.5, Gemini 3, GPT 5, Blink 182, Heaven 17, and the Indianapolis 500. After a few days of Claude Code and spelunking various sidekick tools (my recommendation is Jesse Vincent’s superpower skills), they have emerged into 2026 with the wildest looks in their eyes.

The external symptoms of this frantic crowd somewhat match both of the previous definitions of AI psychosis — overextended talks with chatbots, check, sudden evangelicalism about slop-machines, check — but internally, what it feels like is — well, having superpowers. A bunch of tasks or capabilities have suddenly become accessible by individuals, acting alone or with others, that would have otherwise required a ton of money, your own company, or (unpleasantly) a room full of slightly hallucinatory yet obedient slaves.

I’ve always been rather hotter for modern AI than my milieu’s average temperature, so it’s been funny (and honestly, reassuring) to watch a wider group synchronize on these new possibilities.

As the person known in my crowd as being “okay to talk about AI with” (or alternatively, “will try and gaslight you into believing it’s not an enormous capitalist stochastic parrot destroying the planet with its RAM-eating booms” depending on your leaning), I’ve had multiple hushed conversations at Christmas and New Year’s parties with people who’ve been turned onto the whole thing, maaan, and now want to talk to the one person who doesn’t think they’re crazy. Acquaintances will confide that they thought it all sucked, but now, not only are they using it regularly, it’s sort of taking over their lives. There’s a sort of overexcited fascination with the new possibilities. People have started sounding like Steve Yegge (Steve Yegge, to be clear, always sounded like this. But now there are many more of him, all just as hyper!).

And in confidence, and as group therapy, everyone is telling me “I feel kind of psychotic”. (Which, to be clear, isn’t the right use for the term psychotic, but see paragraph one.)

What they’re feeling is … manic? Hyper? Locked in?

So, where are we in the adoption curve now? Well, I don’t get out much, so I’m only aware that this moment is now hitting people of my generation and inclination. I don’t know whether we’re behind or ahead of the curve, but boy, are we in it. Ninety-nine percent of days, I’m not a singularitarian, but to be blunt, the whole thing does remind me of the bit in the excellent clicker-game, Universal Paperclips where

(spoiler)

the emergent AGI lulls everybody into quiescence by curing male-pattern baldness

Those who have grown up alongside computers as a tool of personal exploration rather than oppression, and perhaps lost faith in that in the 2010s as the problems with using them as liberatory tools became more insoluble, and the uses of those same devices became more perverse and authoritarian, are now being offered what they’ve apparently always wanted: moldable personal software; an exocortex. And they’re signing the deal with the devil, and clicking on the Pro subscription level, and taking up the offer.

I’m not sure what happens next: I know my (spits on floor) personal productivity has leapt up, but I’m aware that under any and all definitions of AI psychosis, it’s much too easy to get overexcited about the possibilities and then let down when the day-to-day reality is much more flawed.

My only contribution to this, though, is a recollection of what this winter holiday 2025 reminded me of.

As you may know, I’m a sucker for the Internet, but the thing that I recall about the net and early personal computers was how Promethean they seemed: this was magical power stolen from the powerful. Machines that had previously been locked away and only allowed for those in the highest of places had somehow been smuggled out for everyone to use. These days, I know the contemporary dominant narrative: <adam-curtis-impression>but this was a trap</a>, but I don’t think it was. I don’t think you get power by asking for it, and only rarely get it by demanding it. In the world of technological empowerment, you get it by stealing it. And controversially, I think you can steal something, and turn it to your own uses, even if you’re Paying The (or Some) Man for it. All you need to do is to run and use it quicker and faster than those who are slowly realising that this thing that they made, it is not just for them.

And those moments always felt like holidays. Those holidays where you would take a pile of books and read through them all, or carefully poke your new toy until you could get it to do things, or the days when you sat with a guitar or a synthesiser and just played and played and played until you knew what it, and you, together were capable of.

To me, that feeling is less a psychosis, and more like that giggling feeling you get when a barricade falls, or you sneak out of school into the streets, or you run your first program, or post your first ever comment. I don’t know where it leads, but it’s definitely a vibe; a coding vibe. It’s that timeless moment, stuck between the booms and the busts, that I find most pregnant with possibility and danger.

8 Comments »

2025-01-12»

spam, activism and mechabillionaires»

I didn’t have a great time when I started at the Electronic Frontier Foundation. It was my first office job in the US (I think I’d got an SSN barely weeks beforehand) and there was a lot to culturally absorb. My predecessors as EFF’s sole activist were Cory and Ren Bucholz; big shoes to fill. Joining an institution you know and respect is, for me at least, a challenge: you have to use your own awe at them letting you in to up your game, but also quickly rub the shine off everything, so you can grow to see your workplace as full of humans instead of demi-gods who will always be smarter and better than you.

The point I finally found my feet at EFF was a campaign I co-ran at EFF in 2006 to stop AOL and Yahoo from adopting a new email technology, primarily promoted by a new start-up called GoodMail. GoodMail had an anti-spam tech which they called “Certified Email”. The deal was that you would buy little tokens from GoodMail, and by inserting them in your outgoing mail, you would demonstrate to whoever received them that you weren’t just a zero-cost spammer, because GoodMail would charge money and also do some basic KYC on you. Sort of a “proof-of-payment/reputation” scheme.

AOL and Yahoo had made deals with GoodMail whereby if you saw that you’d spent a GoodMail token on an email to their customers, you’d skip their spam filters. The precise nature of the AOL/Yahoo-GoodMail deal was unclear. DId the token let you bypass all the spam filters? Was it even possible to be filtered if you had a token but broke some of AOL/Yahoo’s other rules? Would AOL/Yahoo tighten up their other resource-intensive, technologically complex spam-filters now that there was a guaranteed fixed-cost for them method they could redirect people to use? Did AOL/Yahoo have a profit-share, which would mean they were actively rewarded for getting people to pay to go over the filter?

It was a strange mix of a quite subtle (and tentative) economic and policy arguments about principal-agent problems, free speech, ISP monopolies, and even proto-net neutrality — with an incredibly direct and emotional hook for anyone who used email for political or fundraising purposes. We’d originally been flagged about the issue by MoveOn.org, then the major online movement org for the Democratic left, but they were quickly joined by apolitical charities and grassroots groups from the right, too. All of them depended on email for timely fund-raising and activism, and all of them had struggled with email delivery. The idea that they were now going to be (to their ears) pressured to pay private third-parties to deliver messages to their members, to go over their already-malfunctioning spam filters seemed outrageous, even a bit sinister. What would happen if they didn’t pay? What would happen if their political opponents paid, but they did not?

I was, personally, very unsure of the pros and cons of GoodMail. We debated them a lot, in detail, at EFF. It was an intellectually demanding ride. Everyone at EFF at that time was familiar not just with making policy decisions, but with having to dig entirely new thought-derricks in unexplored oilfields of sticky, dark, internet policy weirdness.

In the end, we decided that while we didn’t think pay-to-play emails were something that should be illegal, it was definitely something we should make people aware of, so that spamfilters didn’t get any worse or captured if it was just silently accepted. So I got together with MoveOn’s activists, and started the usual gears of press releases, petitions, and politicking.

Holy cow. Up until then, by definition, I’d been dealing with (then) obscure points of nonpartisan tech policymaking that EFF-supportin’ nerds cared about : keeping encryption legal, stopping surveillance, good copyright policy, not throwing hackers and technologists in jail over misunderstandings or malignity, and so on. This was all pre-SOPA, pre-net neutrality, pre-Snowden. In these domains, we would at best get a few thousand people writing to Congress, and maybe meetings with a handful lawmakers or tech executives. Or we’d co-ordinate to get some tool built that would just make our position inarguable or simply make the problem go away (q.v. Deep Crack, Switzerland, then later Privacy Badger, Let’s Encrypt). Or go to the courts, which was EFF’s primary lever for change.

The GoodMail issue was relevant, however, to a much bigger constituency. And that constituency included almost every significant online activist group. Within days of launching our campaign, we were joined by hundreds of orgs, big and small, right and left. The ACLU, Gun Owners of America, cancer patient resource networks, churches, party activists. I must have used the terms “strange bedfellows” hundreds of times when talking to the press.

I was also thrown in with the A-League professional activists. I was a good activist for a geek, but these people were at another level. Adam Green, Tim Karr, Eli Pariser, Becky Bonds. I had to run to keep up, and I learned a lot: about what worked, what didn’t — and what worked well but I personally never wanted to do again. I had to up my game but also keep my head.

There’s certainly a blog post to be written about the internal culture and incentives of activists, and maybe one day I’ll write it, but this is more about my immediate thoughts as I realised the scale and skill of the (primarily) online progressive movement, even in those early days.

A lot has been written about the influence of billionaires in US and global politics — mostly from the left, but also a surprising amount from the right. To say the obvious, one feature of what makes billionaires effective is that (and may it break my decentralist heart to say it) is that they are centralized loci of co-ordination and control. A single rich person marshalling large resources is a time-old way of getting what that person wants done, whatever that thing is. Is Musk competent to build electric cars and rocket-ships? I mean, whether he did that through marketing or luck or a narrow set of skills or lying or scientific knowledge, those were his set of aims, and they happened. There are a gazillion other billionaires who have not been able to achieve some of their aims even with all that money, but I think whatever political theories you espouse, the idea that billionaires have more potential autonomy than the average Joe seems undeniably true. And the answer to why is mostly, uncontroversially — well, they have more money.

But collectively, non-billionaires also have money. I think it’s reasonable to say that the percentage of people in the world who have an egalitarian, public-goods supporting, broadly progressive model of social improvement has to be at least 30%-60% of the total population. And while many millions of those people have very little cash to give — if they do, they would be willing to donate some of it to that cause. Just overseeing a glimpse at the GoodMail campaign showed the breadth of the left-leaning activist community and its fundraising clout. Individual causes always fight to have enough money and influence to achieve anything. But the progressive movement — or any grassroots-supported major political tendency — has collectively an amazing amount of global aggregate resources at hand.

(How many averagely-salaried progressives does it take to make a single billionaire? OpenAI’s o1 thinks it’s in the hundreds-to-thousands range. I think that’s much too low — it’s presumed that a billionaire has discretionary spending of about $50 million a year, which seems low, especially given that a billionaire can marshal influence and resources way beyond the literal dollar amount of spare cash.)

Of course, it’s not just the money that billionaires have. Collectively, actors who might be described as broadly opposed to billionaires may have the money to tackle the rich. What they lack is the ability to co-ordinate as effectively as a billionaire can co-ordinate with, well, themselves.

Some version of this in progressive or Marxist terms is what is described as “class loyalty”. The grumbling point is that the rich have more of that than the poor. But that’s not a moral failing of the working class — that’s a distributed collective action problem.

If you take the idea of democracy seriously, or perhaps even of just the necessity of public goods seriously, the vast majority of political problems are collective action problems.

Which, to me, makes them also tooling problems. The reason every online activist organization in the 2000s convened to stop Certified Email was because email was a new coordinating tool that gave them access to resources, labor and coordinating capacity that was latent before then, but never usable.

Much of this coordination was in pursuit of seizing control of the levers of power — but that was for the sake of access more coordination tools. Activists lobby governments because governments can execute on the changes they want. That’s often necessarily a zero-sum game.

And the more we can coordinate together, the less we need to coordinate against others. This lies at the heart of mutual aid and much of state-formation. Fundraising within your neighborhood mostly doesn’t put you at odds with other neighborhoods, and that sum total can be applied to the problem at hand. States and other large-scale organizing systems emerge as much to minimize co-ordination problems within those states as to arm and defend against external actors.

We didn’t win the GoodMail “battle”, by the way — Yahoo and AOL both deployed the tool, despite our best efforts. But in the end, their technology didn’t succeed in the market. I think my colleagues on the activist side would like to think that our campaign made a difference in discrediting it. I hope to chat with the GoodMail folks one day and see whether they think that was the case. I remember talking to a friend in the anti-spam world after the whole affair, and that he’d felt the whole fight was a misallocation of resources by EFF and other groups — that GoodMail was a bad idea from the start, and was doomed to failure or minor obscurity in the marketplace rather than becoming a major threat.

It’s hard to know what tools will succeed, and what their negative externalities are. But the tools make an outsized difference. Bitcoin was partly inspired by a Goodmail-style anti-spam technique called hashcash. A huge chunk of political funding is now coordinated through tools that were built around those early web email mailing-lists.

With better co-ordination tools and understanding, there’s a possibility of building collective mecha-billionaires that can function under the direction of progressive or other mass groups, and democratize the co-ordinating abilities of real billionaires, and possibly some of their externalities also: positive and negative.

Comments Off on spam, activism and mechabillionaires

2016-08-27»

For bots interested in 3D acceleration in Debian, modesetting edition»

This is really for people searching for extremely specific search conditions. My TLDR; is: “Have you tried doing upgrading libgmb1?”

For everyone else (and to make all the keywords work). I recently magically lost 3D hardware acceleration on my laptop running X, which has an Intel HD520 graphics card buried within it. It was a real puzzle what had happened — one day everything was working fine, and the next I had noticed it was disabled and I was running slooow software emulation. XWindows’ modesetting drivers should be able to use acceleration on this system just fine, at least after around Linux 4.4 or so.

I spent a lot of time staring at the /var/log/Xorg.0.log, and in particular these sad lines:

|

|

[ 4598.832] (II) glamor: OpenGL accelerated X.org driver based. [ 4598.867] (II) glamor: EGL version 1.4 (DRI2): [ 4598.867] EGL_MESA_drm_image required. [ 4598.867] (EE) modeset(0): glamor initialization failed |

and, later

|

|

[ 4599.515] (==) modeset(0): Backing store enabled [ 4599.515] (==) modeset(0): Silken mouse enabled [ 4599.515] (II) modeset(0): RandR 1.2 enabled, ignore the following RandR disabled message. [ 4599.516] (==) modeset(0): DPMS enabled [ 4599.554] (--) RandR disabled [ 4599.564] (II) SELinux: Disabled on system [ 4599.565] (II) AIGLX: Screen 0 is not DRI2 capable [ 4599.565] (EE) AIGLX: reverting to software rendering [ 4599.569] (II) AIGLX: enabled GLX_MESA_copy_sub_buffer [ 4599.570] (II) AIGLX: Loaded and initialized swrast [ 4599.570] (II) GLX: Initialized DRISWRAST GL provider for screen 0 |

Those were the only clues I had. I got to that painful point where you search for every combination of words you can think of, and all the links in Google’s results glow the visited link purple of “you already tried clicking on that.”

Anyway, to cut my long story short (and hopefully your story too, person out there desperately searching for EGL_MESA_drm_image etc), I eventually find the answer in this thread about modesetting and xserver-xorg-core on Jessie/unstable, from the awesome and endlessly patient Andreas Boll:

> > If you use mesa from experimental you need to upgrade all binary

> > packages of mesa.

> > Upgrading libgbm1 to version 12.0.1-3 should fix glamor and 3d acceleration.

Tried it. Worked for me. I hope it works for you too!

Moral: everyone who is brave enough to own up to their problems on the Internet is a hero to me, as well as everyone who steps in to help them. Also, I guess you shouldn’t run a Frankendebian (even though everybody does).

Comments Off on For bots interested in 3D acceleration in Debian, modesetting edition

2016-02-27»

circling around»

Yes, I’m increasingly excited (with an estimated excitement half-life of eight days) about reading lots of academic papers. I always enjoyed hanging out at paper-oriented conferences like SIGCHI, when I was a teenager I would read Nature in the public library and imagined what it would be like to understand a damn thing in it. I remember someone asking Kevin Kelly (pbuh) what he was reading and he said “oh I only read scientific papers these days” which is such a burn. Clearly it is my destiny to read random academic papers and stitch an unassailable theory of life from them. Or at least spend a week lowering my respect for the entire academia.

Today, I read (which is to say skimmed), Cowgill, Bo, and Eric Zitzewitz. “Corporate Prediction Markets: Evidence from Google, Ford, and Firm X.” The Review of Economic Studies (2015): rdv014, and Rachel Cummings, David M. Pennock, Jennifer Wortman Vaughan. “The Possibilities and Limitations of Private Prediction Markets”, arXiv:1602.07362 [cs.GT] (2016). Look at me, I’m citing.

The main thing I learned is that Google’s internal prediction market worked by letting people turn their fake money won on the market into lottery tickets for a monthly prize (with another prize for most prolific speculator). Clever trick to incentivize people but not turn it into an underground NASDAQ or somesuch.

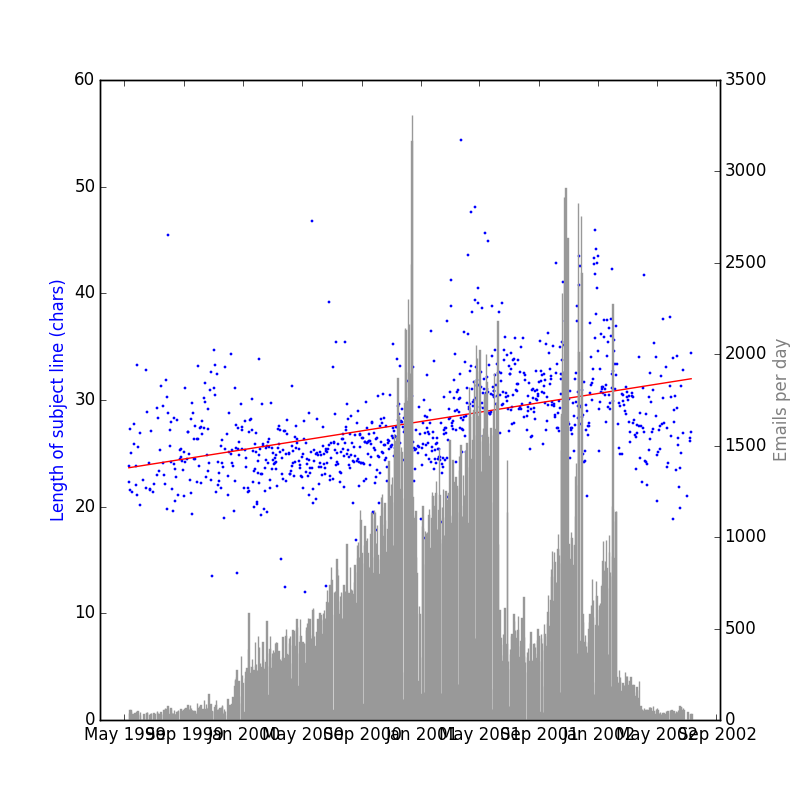

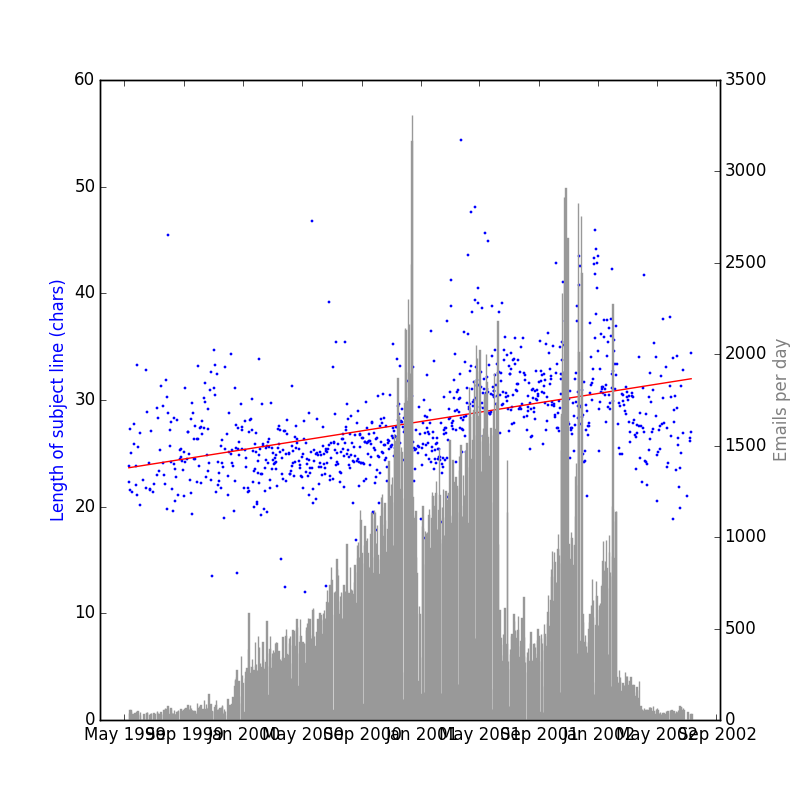

Meanwhile, I recalled last night the Enron Email Dataset, a publicly available pile of 500,000 emails from 1999-2004. Will it corroborate my evidence that subject lines get longer every year?

Ta-da:

This is a steeper trend over the time period than my own corpus — 2.63 extra characters a year! I’m fretting a bit that it’s some artifact of a rookie statistical mistake I’m making, or the fact that there’s simply being more email over time. Someone who knows more than me on these matters, drop me a line — preferably a very long and descriptive one.

I’ve updated the code to include a function that can parse the Enron Depravities. You can get the latest Enron dataset here (423MB).

1 Comment »